Archives

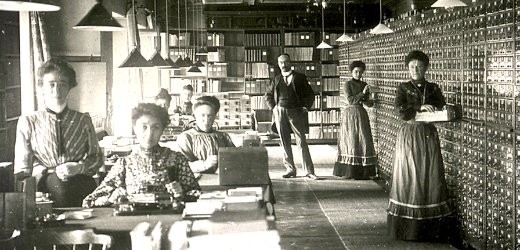

Museums, libraries, archives and repositories hold an overwhelming wealth of reference and information. Notably the environments themselves are often evocative as they suggest our desire to collect, remember, and cherish. As infinite amounts of knowledge are accrued further desires are fulfilled, to identify, classify and store. What is displayed to the curious only intimates what is contained behind closed doors in storage. Along corridors lined by filing cabinets filled with knowledge and rows of towering shelves weighted by boxes packed with posterity, these treasures are kept. A tranquility reigns in these spaces as scientific classification and archiving systems rigorously pacify with colour-coding, alphabetical and numerical order, signs, labels, and index cards.

The Father of Information Science

Paul Otlet (1868-1944), had a vision to create a global network of knowledge called the ‘Mundaneum’. He worked unrelentingly to index and catalogue as much published works as was possible, and the Mundaneum opened in 1920. It employed a revolutionary index-card filing system which had been designed by Otlet, to answer mail-order information requests by hand. He is considered to be the Father of Information Science.

Table of the Animal Kingdom, 1735, Carl Linnaeus, System Naturae

The Father of Modern Taxonomy

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), devised a system of classification for plants and animals that has formed the basis of all other future studies in the field as detailed in his seminal book Systema Naturae (1735). It uses a hierarchy that is divided into kingdoms, classes, orders, genus, species and rank. He known as the Father of Modern Taxonomy and is also renowned for inventing the index card.

‘Love Will Decide What is Kept and Science Will Decide How it is Kept’

In discussing the difficulties encountered and methodologies employed by curators of collections, Sue Prichard provides an illuminating account in “Collecting the Contemporary: ‘Love Will Decide What is Kept and Science Will Decide How it is Kept’” (The Textile Reader, Hemmings, 2012).

Knowledge is almost as valuable as wisdom and similarly an object’s fiscal value is irrelevant when compared to the sentiments and memories that it may invoke. We are all collectors, curators and archivists of our own treasures. They may be as precious as baby-teeth nestled on a bed of cotton wool in a matchbox, love-letters carefully folded in an envelope, photos displayed in a scrapbook or as unassuming as spoons, honeypots or figurines. They are kept.

The influence of scientific classification is evident in the work of contemporary artists such as, Teddy Bear (Un) Natural History by Stephanie Metz and the fungus and moth textile sculptures by Mr. Finch. Our inclination to collect, curate and archive is conveyed in the Assemblage Sculpture of Joseph Cornell. The rich and often overlooked relationship between Art and Science is often seen in the illustrations of Botanists such as Maria Sibylla Merian.

There are many exhibitions that reference some of these themes in their considered display techniques. Chanteh – Tribal Textiles from Iran (2012 – 2013), used ordered clusters as a striking display technique in the arrangement of textile objects that may have been lost if viewed individually. Madame Gres: Couture at Work (2011) used a most powerful and evocative display technique whereby the dresses were exhibited amongst the classical statues of the museum’s collection in the handling cases used for the transportation and storage of fragile objects. Spectres: When Fashion Turns Back (2005), used set design, lighting and shadow to convey historical referencing in contemporary fashion.

Frameworks

Whilst the acquisition of knowledge through research is marvelously rewarding it can also become overwhelming. Clear directions are deviated from as tree-lined avenues may turn into lanes that wind down boreens, with enticingly overgrown paths and just as you see a tunnel in the hedgerow and are burrowing down a warren, another avenue is discovered that you cannot possibly leave unexplored. And where were you going in the first place? So it becomes necessary to devise a system of classification for your own research, with typologies and taxonomies that are painstakingly arranged through gradation, stratification, even nuance, until finally you realise that they may actually overlap. There is a beauty in the peace, organisation and clarity resulting from such systems. From the structure, boundaries and rigidity of these orders it is possible to release an abundance of creativity, ideas and outcomes.

It is worth recognizing that the breadth and scope of research may be an outcome in and of itself, a finished piece with intrinsic beauty in the simplicity of presentation and complexity on inspection.